Lt. Albert F. Hegenberger

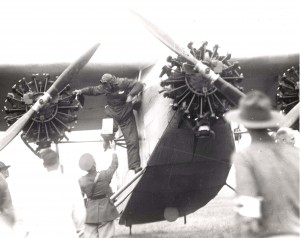

Still unknown to the world was the fact that the Army was about to make the flight, a tantalizing project since the Navy’s conquest in 1919 of the Atlantic, and the near victory over the Pacific in 1925. Not only had the navigation equipment under development proved out, the Army Air Corps successfully tested the new Fokker C-2-3 Wright 220 airplane (A.S. 22-206) and had assembled men to handle the chore. Directly involved were the best in the Army. As the Navy had done for its world record over-water flights, painstaking efforts were made to choose exactly the right people to handle airborne chores. The final choices were Lieutenant Lester J. Maitland, pilot, and Lieutenant Albert F. Hegenberger, navigator.

Still unknown to the world was the fact that the Army was about to make the flight, a tantalizing project since the Navy’s conquest in 1919 of the Atlantic, and the near victory over the Pacific in 1925. Not only had the navigation equipment under development proved out, the Army Air Corps successfully tested the new Fokker C-2-3 Wright 220 airplane (A.S. 22-206) and had assembled men to handle the chore. Directly involved were the best in the Army. As the Navy had done for its world record over-water flights, painstaking efforts were made to choose exactly the right people to handle airborne chores. The final choices were Lieutenant Lester J. Maitland, pilot, and Lieutenant Albert F. Hegenberger, navigator.

Lieutenant Lester J. Maitland, pilot, and Lieutenant Albert F. Hegenberger, navigator were selected to fulfill the Army’s dreams to successfully cross the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii. Not only had the navigation equipment under development proved out, the Army Air Corps successfully tested the new Fokker C-2-3 Wright 220 airplane (A.S. 22-206) and had assembled men to handle the chore. Directly involved were the best in the Army.

Hegenberger was Chief of the Instrument & Navigation Unit, Materiel Division, Wright Field which, for the most part under his leadership, had been studying problems of such a flight—and of trans-oceanic flying in general—since the summer of 1919. A program for such a flight had been laid out in this unit in February, 1920. Since 1919, Hegenberger tested every known navigation instrument and method, including regular “blind” flying tests and engineering of the equipment’s development. He completed a course of instruction in navigation at the Navy’s school at Pensacola in February, 1920. Commander John Rodgers told Hegenberger of his 1925 experiences over (and atop) the Pacific, as did fellow officer on the PN-9 No. 1, B. J. Connell (by then holder of world and U.S. performance records).

An able and zealous group of select civilian employees from the Army rounded out the team, consisting of the following:

- L. D. Hendricks, Laboratory Assistant

- Fred Herman, Aeronautical Engineer

- Bradley Jones, Navigation Engineer

- James Rivers, Foreman, Airplane Mechanic

- Clayton C. Shangraw, Radio Engineer

- Victor E. Showalter, Navigation Engineer

- Ford Studebaker, Radio Engineer

The Army’s Materiel Division, in pursuing a California to Hawaii flight during the eight-year effort in collaboration with other agencies, played a principal role in the development of various instruments such as bank and turn indicators, flight indicators, air sextants, compasses, ground speed and drift indicators, computers, and other equipment, as well as special navigation methods. These developments involved hundreds of test flights, including many through clouds, fog, and darkness. During tests, the ultimate flight from California to Hawaii was simulated numerous times. At last, it was felt that satisfactory instruments and methods had been developed for oceanic flying.

Lieutenant Hegenberger was given responsibility to prepare the plane, including installation of special equipment, final arrangements of fuel system, engines, pumps, and airborne facilities, among other requirements. Because the navigator had to function as radio operator and pilot as well, a special passageway was provided between the front cockpit and the navigator’s cabin in the rear, necessitating the removal of one fuel tank. Then came further tests.

On June 15, still shrouded in military security limitations, the Army Fokker took off from Wright Field for its Oakland destination preparatory for the big flight. In one plane with Maitland and Hegenberger were Messers Herman (to check fuel consumption), and Rivers (for airplane and engine maintenance). Airborne at 10:50 a.m., the C-2 landed at Scott Field, Illinois, then went on to Hat-Box Field, Muskogee, Oklahoma, where the quintet remained overnight. Two stops were made the following day, at Dallas and Kelly Field, Texas.

It was at Kelly that the Wright Field crew found a large crowd, cameramen and reporters waiting for them. Headquarters in Washington had officially announced the flight to Hawaii; they were told about it upon landing. A B-5 compass was repaired, as was the radio and a defective inductor compass. The next day they flew to El Paso, Tucson, and then to Rockwell Field in San Diego, at 5:25 p.m., June 20th. Here, minor adjustments were made. At Mr. Herman’s recommendation, a 70-gallon fuel tank was installed, bringing the total fuel capacity to 1,120 gallons, ample now for the flight to the mid-Pacific.

On June 25, the C-2 left Rockwell for Crissy Field, picking up the new radio beacon 125 miles south of San Francisco. A smooth landing was made there at 3:18 p.m., ending 2,815 miles of flight in 33 hours and 9 minutes. Monday morning, June 27, the plane settled onto Oakland’s 7,200 foot runway. The plane was topped with fuel plus almost 40 gallons of oil. Taken on board was the inflatable raft and food for the trip. Preparations continued for the arduous trip.

Maitland and Hegenberger denied any interest in racing, for prizes or “first” distinction. They felt the desirability to link up Hawaii and the mainland by air was purely for the advancement of aviation, stating this flight would be a test of the navigation equipment Hegenberger and his Army unit had been developing for years. Another stated objective of the long-range flight was to test the performance of the new radio beacon installed by the Army Signal Corps on the island of Maui and reaching to San Francisco. Finally, it was felt certain that much valuable data could be obtained for use in the establishment of regular commercial airline service over the route. Encouraging commercial aviation by the establishment of airways was the job of the military, they said; this flight fell in the Army’s peacetime mission.

Shortly after 7 a.m. on June 28, 1927, the Army pair shook hands with their crews who had worked so hard and climbed into positions in the airplane. Left behind were their parachutes, mandatory in the Army since 1922; they would be of little use in open seas.

Major General Patrick, Chief of the Air Corps, after inspecting the airplane, wished the young flyers good luck. Then the BIRD OF PARADISE started up, its three Whirlwinds humming noisily. The plane made its way along the runway. It was 7:09 a.m., June 28, 1927. At the 4,600 foot mark, and a speed of 93 mph, the huge plane lifted off the ground. Other Army planes joined the rising Fokker in escort, as it edged higher in the sky. The plane dipped its wing in salute to the men and equipment left behind. At the 2,000 foot altitude, Maitland and Hegenberger passed over the Golden Gate then headed on the first course of the Great Circle to Maui, where the radio beacon was to tie in with the station in San Francisco.

THE FLIGHT

For the first 500 miles they encountered strong crosswinds and after that a very strong tailwind which increased their airspeed to 108 mph. They flew close to the sea during daylight hours at an altitude of 300 feet. The flyers were pleased at the sight of their first checkpoint, the Army transport Chateau Thierry steaming for San Francisco. Then the right engine sputtered due to an overflow of oil being drawn into the carburetor intake, but improved in 10 minutes. In the first hour, the induction compass failed, making it necessary to rely on the B-5 compasses. At 7:45 a.m., the radio beacon was first tuned in. An hour later, however, its reception suddenly cut out. One tube was changed, then two batteries; reception came in again, this time lasting only 30 minutes. Failing to revive the set, Hegenberger reset his course to the steamship SONOMA, later sighted at 2:34 p.m. Navigation was by dead reckoning and solar observations.

At 7:45 p.m. the PRESIDENT CLEVELAND and the BIRD OF PARADISE were in radio communication, the ship reporting having received a weak signal. Maitland flew to 10,200 feet to get over the clouds for celestial observations. At about 1 a.m., Hegenberger heard the beacon’s signals and made course corrections while he could. Forty minutes later the reception again cut out, this time for the remainder of the trip. This was a great official disappointment.

They flew without incident until about half-way, at this point relaxing sufficiently to discover hunger pangs. Searching for food which was supposed to have been stowed aboard for them, none could be found by either flyer. They settled back for a hungry trip. Suddenly, however, the center engine sputtered, causing them to lose altitude down to 4,000 feet. For one hour and 40 minutes, two good engines carried the crew through clouds and total darkness. Hegenberger used a pocket flashlight to read instruments and charts throughout the night. The engine trouble was determined to be carburetor icing when frost appeared on the outboard engine instruments. No preparations had been made for applying exhaust heat to the carburetor because the high altitude was not expected and heaters were left behind. At the 4,000 foot mark the warmer air temperature gradually cleared the carburetor and allowed Maitland to climb to a safer altitude, 7,000 feet, where he stayed for the rest of the flight.

At 3:20 a.m., tired eyes beheld a wonderful sight, the lighthouse on Kauai five degrees to the left of the plane’s nose. When the shore line was approached, the island’s contour became familiar—one they knew so well from past inter-island flights. Oahu was 75 miles from Kauai; daybreak would not occur for about another hour. Maitland and Hegenberger chose not to jeopardize a successful completion to their flight by approaching mountainous Oahu in heavy clouds, rain and total darkness. They decided to circle Kauai until daybreak, slowing down to 65 mph. They passed over Barking Sands.

SUCCESS!

Crossing the channel to Oahu at 750 feet just below an unbroken cloud layer, they saw a Very pistol fired from Pearl Harbor (later learned as coming from Commander M. H. McComb). Their speed was boosted to 115 mph and soon they found themselves 500 feet over Schofield Barracks. Below them at Wheeler Field were thousands of people and many cars, then the white smoke of a welcoming 75-millimeter field gun’s salute. Maitland circled the field once for the anxious spectators then came to a fine landing at 6:29 a.m., June 29, 1927, 2,425 miles having been flown from California to Kauai in 23 hours. It was a total of 25 hours and 49 minutes when the three-engine plane touched Wheeler’s famous runway. Maitland reflected on his 1918 flight between the islands, in contrast. The future Episcopal minister thanked God silently.

Crossing the channel to Oahu at 750 feet just below an unbroken cloud layer, they saw a Very pistol fired from Pearl Harbor (later learned as coming from Commander M. H. McComb). Their speed was boosted to 115 mph and soon they found themselves 500 feet over Schofield Barracks. Below them at Wheeler Field were thousands of people and many cars, then the white smoke of a welcoming 75-millimeter field gun’s salute. Maitland circled the field once for the anxious spectators then came to a fine landing at 6:29 a.m., June 29, 1927, 2,425 miles having been flown from California to Kauai in 23 hours. It was a total of 25 hours and 49 minutes when the three-engine plane touched Wheeler’s famous runway. Maitland reflected on his 1918 flight between the islands, in contrast. The future Episcopal minister thanked God silently.

When the huge Fokker came into view from the northwest of Wheeler Field, the many thousands of people previously on hand had dwindled to a few thousand. Many had gone home. Some thought of Rodgers plight, others of the impracticability of a land plane making the crossing at all. Many, however, waited for the moment of success. They were elated to see the plane but surprised to see it flying alone. A welcoming squadron of 12 planes from Luke and Wheeler had been circling in the air near Diamond Head for about 30 minutes, waiting to act as proud aerial escorts.

When the huge Fokker came into view from the northwest of Wheeler Field, the many thousands of people previously on hand had dwindled to a few thousand. Many had gone home. Some thought of Rodgers plight, others of the impracticability of a land plane making the crossing at all. Many, however, waited for the moment of success. They were elated to see the plane but surprised to see it flying alone. A welcoming squadron of 12 planes from Luke and Wheeler had been circling in the air near Diamond Head for about 30 minutes, waiting to act as proud aerial escorts.

It was a joyous occasion, as dignitaries, friends and well-wishers welcomed the flyers. Maitland and Hegenberger later laughed only half-heartedly with their friend, Lieutenant John Griffith, who had found the missing food while checking the plane’s interior. It sat quite undisturbed and ready to consume under Hegenberger’s plotting board.

It was a joyous occasion, as dignitaries, friends and well-wishers welcomed the flyers. Maitland and Hegenberger later laughed only half-heartedly with their friend, Lieutenant John Griffith, who had found the missing food while checking the plane’s interior. It sat quite undisturbed and ready to consume under Hegenberger’s plotting board.

A young Hawaiian resident, originally from the Philippines, Jose Galura watched the historic landing. His comments 37 years later were, “It was a great thing those Army flyers did. I knew Hawaii would now be more famous because these were just the first to fly to the Islands. Soon there would be civilians coming by airplanes just like on ships.”

The flight was an unprecedented success. This time the eyes of the aviation world—and the public—would not again turn away from Hawaii, as a new phase of aviation dramatically made its entrance.

The feat was hailed by the War Department and the press. The Honorable F. Trubee Davison, Assistant Secretary of War, stated “—a new vista of communication between America and its overseas positions” had been opened by the Army, underscoring the progress made in aerial navigation. He went on, “The flight is unquestioningly one of the greatest of aerial accomplishments ever made.”

Davison was “particularly pleased that two Army Air Corps officers, operating an Army plane built for no other purpose than Regular Army use, were the first to negotiate the flight to Hawaii.” He amplified further, “The thought behind the Army’s project was not to have an Army plane be the first to cross the Pacific but to gather data which would be of value in promoting air traffic between California and Hawaii. The flight was contemplated in the interest of aviation and not as a quest for a unique record.”

Davison was “particularly pleased that two Army Air Corps officers, operating an Army plane built for no other purpose than Regular Army use, were the first to negotiate the flight to Hawaii.” He amplified further, “The thought behind the Army’s project was not to have an Army plane be the first to cross the Pacific but to gather data which would be of value in promoting air traffic between California and Hawaii. The flight was contemplated in the interest of aviation and not as a quest for a unique record.”

The New York Tribune was prophetically accurate in commenting, “—the cheering crowds at Honolulu see themselves emerging from the lonely isolation of the mid-Pacific and many already are envisioning a future in which their islands will be a junction point for fast passenger and freight services to Oceania, Australia and the Far East.”

The Chicago Tribune stated: “This country has the genius requisite to deal with the scientific problems of aviation that still await solution. It has the enterprise, the courage, the skill and the material assets necessary to maintain the supremacy it has won and to use it beneficially for defense and for progressive peace-time objectives. Aviation needed a dramatic challenge to the popular and business mind, and now the challenge has been furnished in a series of remarkable flights.”

The Chicago Tribune stated: “This country has the genius requisite to deal with the scientific problems of aviation that still await solution. It has the enterprise, the courage, the skill and the material assets necessary to maintain the supremacy it has won and to use it beneficially for defense and for progressive peace-time objectives. Aviation needed a dramatic challenge to the popular and business mind, and now the challenge has been furnished in a series of remarkable flights.”

The Minneapolis Journal stated that the achievement, “—opened an aerial avenue over the eastern reaches of the Pacific, even as Lindbergh opened an aerial avenue over the Atlantic.”

Maitland and Hegenberger soon boarded the MAUI for a long but comfortable ride to the mainland. Three PW-9s took part in an aloha flight. Island hospitality became marred by tragedy when the pilot of one, attempting to execute a roll, plunged to a watery death. During memorial services that followed, Martin Bombers dropped flowers on the spot in the ocean where their aerial comrade had fallen.

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.

Related content

Fly by Stars When Radio Beam Lost Reprinted from the Honolulu Advertiser, January 30, 1927

Photos of Hegenberger & Maitland Flight

Bird of Paradise A recap of the Hegenberger-Maitland flight, February 15, 1977.

The Flying Bird of Paradise Article from the Aerospace Historian, March 1979