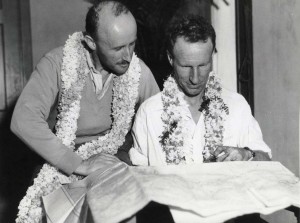

Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith

Our attention is brought back to Oakland Airport. The day was May 31, 1928. The airplane was a Fokker with three new Wright Whirlwind J-5 engines. The flight was to be to Hawaii and on from there to Fiji and Australia. The event was the first trans-Pacific flight. Hawaii was about to function for the first time as the crossroads of the Pacific in the air, as it was by sea.

Our attention is brought back to Oakland Airport. The day was May 31, 1928. The airplane was a Fokker with three new Wright Whirlwind J-5 engines. The flight was to be to Hawaii and on from there to Fiji and Australia. The event was the first trans-Pacific flight. Hawaii was about to function for the first time as the crossroads of the Pacific in the air, as it was by sea.

Australian Squadron leader Charles Kingsford Smith climbed aboard his second-hand airplane (built of two Fokkers and previously flown on an arctic exploration). Also entering the plane were Charles P. T. Olm, co-pilot and another Australian; Harry W. Lyons, navigator from Honolulu; and James W. Warner, radio operator from the United States.

The mother of ill-fated DALLAS SPIRIT navigator, Albert Eichwaldt, who lost his life with Captain Erwin while searching for the lost Dole Air Derby planes, presented her missing son’s ring to the pilot, kissed and wished Kingsford-Smith good luck. The SOUTHERN CROSS was provided with 1,350 gallons of gasoline and then 4,000 spectators bid the tri-motored monoplane a noisy farewell as it lumbered heavily down the runway on an ambitious journey.

Preparations for the flight had been in the making for about a year, and the crew was glad to be on the way. The flyers were to be delayed five minutes, however, when 500 feet down the runway one engine faulted. At 8:53 a.m., another take-off was attempted, this time successfully.

Not only did the radio work well on the long flight, so did everything else–including the weather. This was a flawless flight, the first to function perfectly in all respects on this route. Flying at between 70 and 90 mph, the large Fokker consumed 27 hours and 27 minutes of flying time to Wheeler Field. A number of Army planes in the air at the time took on the role of aerial escorts from Diamond Head past Pearl City to Wheeler. Landing at 9:50 a.m., the first foreigner-flown plane to land in Hawaii was witnessed by thousands of people, including Governor Farrington, Dole Air Derby winners Goebel and Jensen, globe-circling Army Captain Lowell H. Smith, and Hawaii air pioneer Charles Stoffer.

The happy quartet was taken to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel for celebrations then rest, while a repair crew went to work on the starboard engine in preparation for the next leg of the lengthy journey. Jensen and Stoffer flew the Star Bulletin’s films of the event to the publishing house in Honolulu. Others were delivered by automobile and by motorcycle.

During a Honolulu reception in his honor, the new air hero praised the pilots who made the flight before him. Kingsford-Smith was impressed with America’s interest in Pacific flying, stating it was his hope that his own flight would help establish air travel across the route he was taking.

At 4:30 p.m., June 2nd, the heavily loaded SOUTHERN CROSS left Wheeler for Barking Sands on Mana, Kauai, where a special runway had been constructed for its take-off for Suva, Fiji. Accompanying it was the BIRD OF PARADISE with Captain Lowell H. Smith at the controls. Both planes landed on Kauai at 5:57 p.m. and mechanics wasted no time in beginning the arduous task of tuning the plane for its 3,180 mile flight leg to Suva.

At 5:20 a.m., June 3rd, Kingsford-Smith took off from the sandy runway. Fighting heavy winds, rain and bumpy air, he landed in the Albert Cricket Grounds in Suva, 34 hours later. It was the longest flight ever made over continuous seas and another perfect flight. Now only 1,762 miles remained to be covered. But like Wheeler, the cricket grounds were too short for safe take-off. A suitable facility, Naselai Beach, was found which could handle a long run with full fuel loads, so the airplane was flown there and gasoline brought to it. On June 9, the dauntless crew made for the pilot’s homeland.

The last leg went well, except for two hours of severe storms. At one point, the plane was thrown 140 miles off its course and the crew became extremely cold. Coming close to Brisbane, the SOUTHERN CROSS picked up its aerial escort and proudly came in to land. A total of 7,230 miles had been flown in 83 hours and 72 minutes, an incredible performance.

The crew was given $25,000 by the Australian government in recognition of this achievement. Plans to raise a fund of $100,000 in addition, were announced. The flight’s financial backer, Captain Allan Hancock, presented to the intrepid airmen the airplane which conveyed them to international prominence and a well-deserved place in history.

Kingsford-Smith had proved a great deal. Probably most important was the dependability of aircraft—of the land type–at that—to make extensive over-water flights of great distances. Next, and of direct interest to Hawaii and the millions who were to travel by air to and through the Islands for years to come, was revelation of the fact that the mid-Pacific springboard worked well, making flights to other lands feasible. This accomplishment in the air was to be the last assault on John Rodgers’ route (and beyond) for almost six years, as the springboard was removed from service for a period of test and improvement, change and modification. It was being made ready to function on a grand and lasting scale to truly qualify Hawaii as the air port-of-call for the world.

The illustrious aviation name of Kingsford-Smith was to appear again to the world, in 1934. Following their 1928 flight across the Pacific, Sir Kingsford-Smith (now knighted) and Charles P. T. Ulm had formed and operated the original Australian National Airways. Their aircraft were the SOUTHERN CROSS and replicas of the Fokker, built by A. V. Roe, called Avro 10. Among pilots hired to fly with ANA was Patrick Gordon Taylor, World War I combat flyer, also an Australian. Following the tragic disappearance of an ANA airplane (1931), the pioneer airline folded due to heavy financial losses.

Sir Kingsford-Smith and Taylor pioneered flights across the Tasman Sea, from Australia to New Zealand, in the SOUTHERN CROSS (during 1933 and 1934). Four flights in all were made and then the pair embarked on a great adventure: making a flight from Australia to North America, via enroute islands. By it, they hoped to create interest in the establishment of a regular trans-Pacific air service between the two continents. A single-engine landplane was selected for two reasons. With only one engine, there was half the risk of a forced landing at sea, in case of engine failure; it would inspire confidence in regular passenger and mail service by the four-engine flying boats projected for the route.

The selected airplane was a Lockheed Altair, named LADY SOUTHERN CROSS. During an exploratory flight they discovered excessive fuel consumption at recommended power settings, ruling out safe flight from the first stop—Fiji to Hawaii. Performing tests of different settings, one was selected which would give them an extra two hours’ flying time against a 20-knot headwind.

Mid-October, 1934, the flyers were ready for their 7,000-mile journey. From out of the crowd of well-wishers at the Brisbane airport rushed a woman with a white rose in her hand. She gave it to Taylor and he promptly placed it in a buttonhole of his coat. Then Sir Kingsford-Smith powered his airplane to a fine take-off on a track for Fiji. Except for rainy weather east of New Caledonia, during which the wing became damaged, the flight went smoothly. The Altair was brought to a landing in Albert Park, Suva, where the Cricket Field allowed only a 300-yard run. They then flew to Naselai Beach, 20 miles away, for a safer take-off of their heavily loaded airplane. Strong cross winds persisted for a week. Not until October 29 did they get off.

During the night they encountered heavy rains and turbulence. To better see if the rains were easing up, the pilot turned on his landing light. After switching off, both men were appalled to note a decrease on the airspeed indicator from a normal cruise of 125 knots to 90. Within seconds, the plane fell into a stall then began to spin. Sir Kingsford-Smith worked feverishly but was unable to right the airplane. Turning to his navigator, he said, “I’m sorry, but I can’t get her out.” Taylor asked, “Do you mind if I have a go at her?” Permission granted, Taylor called on all his skills and experience but was not able to stop the persistent spinning.

Returning the controls to his pilot, Taylor noted they had dropped in altitude from 15,000 feet to 6,000. Suddenly, the Altair was smoothed out to normal flight attitude. Sir Kingsford-Smith then revealed that the flaps had been inadvertently switched to the down position when the landing lights were turned on, which brought on stalling conditions.

Now relaxed, the pair managed the remaining flight to Hawaii without incident. There being no radio aids between Fiji and Hawaii, Taylor relied completely on his astronomical navigation abilities. They proved to be excellent. At dawn, the Hawaiian Islands came into view. Taylor recalled, ‘I just sat there, filled with a curious sense of gratitude that we had been given the conditions to find these islands, that the engine had never shown a sign of failure in the 25 hours of flight, and the most wonderful sense of anticipation for arrival at Honolulu.”

When Pearl Harbor was reached, a formation of United States aircraft joined the LADY SOUTHERN CROSS on its final Hawaiian run. The landing on Wheeler Field’s green grass was executed perfectly. On hand to greet the pioneers were excited crowds of friendly and happy people. Among them was John Stannage, their radio operator from Tasman Sea flights made earlier. Stannage feigned disgust at Taylor’s dilapidated World War I flying helmet. But the latter refused to surrender his “heirloom.” Being the first international aircraft ever to land in Hawaii, Altair VH-USB was processed by United States Customs and was cleared. Then the heroes were whisked off to Waikiki Beach and the Royal Hawaiian Hotel.

The pair had not slept for 30 hours; they underwent a harrowing experience and were feeling the effects of strain. Nevertheless, Sir Kingsford-Smith invited Honolulu’s mayor for a flight over the city. Back to Wheeler went the trio. Taylor stood by as the sleek airplane was lifted into the air by the skillful pilot. Not three minutes had passed when at 2,000 foot altitude the engine suddenly became silent and the propeller began to windmill uselessly. LADY SOUTHERN CROSS was quickly nosed down and banked for a downwind landing on the field. Pilot and passenger dismounted. Investigation revealed that the airplane was completely out of fuel. Army Air Corps technicians dismantled the fuel system and removed the fuselage tanks. A large crack was found in one tank, though which the extra fuel had leaked out.

The Australians remained in Honolulu four days and nights while the Altair was made ready for flight. On November 3 the final leg of the first west-east flight across the Pacific began. Fifteen hours later, the Altair was at Oakland Airport being swarmed upon by admirers and newsmen. The beautiful white rose came to Taylor’s mind and he was pleased to find it still in his buttonhole. Out of the happy crowed he picked a small boy and presented the flower to him for good luck.

The Australians remained in Honolulu four days and nights while the Altair was made ready for flight. On November 3 the final leg of the first west-east flight across the Pacific began. Fifteen hours later, the Altair was at Oakland Airport being swarmed upon by admirers and newsmen. The beautiful white rose came to Taylor’s mind and he was pleased to find it still in his buttonhole. Out of the happy crowed he picked a small boy and presented the flower to him for good luck.

This was Sir Kingsford-Smith’s second Trans-Pacific flight. For Taylor, however, it was the first of many transoceanic flights to follow during a brilliant 35-year flying career. On this occasion thoughts brought him back to a day in 1917. He was heading for home base in France after shooting down (his Royal Flying Corps unit’s first to fall on the Allied side of the lines) a German plane. This is Taylor’s reflection:

“Flying westward in the stillness, I fancied myself going on with the rhythm of the LeRhone spinning a way of life around the world, a way of peace and understanding instead of a way of war and destruction. Three hour endurance. Three hundred mile range. Not long ago it was a feat for Bleriot to cross 20 miles of the English Channel from Calais to Dover. If my airplane could fly 300 miles it must be possible some day to fly 3,000 miles to join the continents across the oceans.”

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.

Related content

Photos of Kingsford-Smith

Our Conquest of the Pacific Article

The Story of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith Article