Pan American Airways

The first scheduled airline in America was inaugurated in January, 1914, with Tony Jannus hauling one passenger 22 miles from Tampa to St. Petersburg, Florida, in a Benoist flying boat. Losing money, the venture was discontinued after three months. In a few years, however, commercial airlines operated in many areas of the continent.

As for flying to other lands, it took a foreign firm’s activities to accelerate such efforts. In 1925, Scadtka Air Lines was set up in Colombia by a World War I German military aviator. SAL planned to fly to Panama, Central America, Cuba and the United States transporting passengers and mail.

According to Postmaster General New, an airmail contract with the foreign company would be granted unless an American firm came forward. Acting fast, the Army Air Service’s Major Henry H. Arnold and several other officers drew up a proposed airline operation, Pan American, Incorporated, and considered resigning to comprise its leadership. Civilian manned in the final analysis, Pan American was awarded an airmail contract with the Cuban government.

Competitive firms were urged by the leader of one, Juan T. Trippe, to join forces. They formed Pan American Airways, Inc., in 1927, and the Key West to Havana airmail route became theirs. Under the inspired leadership of Trippe, PAA surveyed foreign routes, secured franchises from the governments, and so were able to win contracts at the maximum rate fixed by law. In 1929, the company had four contracts, 44 multi-engine planes, many employees and an optimistic future.

Juan Trippe was interested in trans-oceanic passenger and mail service to the Orient and, with the help of Charles A. Lindbergh, PAA technical advisor, and the company’s chief engineer, Andre Preister, plans were laid out which would take several years to reach flight proportions.

Choosing a flying boat configuration for maximum safety, PAA finalized designs and sent out invitations for bid. Manufacture was to be no easy task. The plane was to safely and comfortably carry crew, passengers, mail and cargo, from California to the Orient and back again, over water on a regularly scheduled basis. In addition, this had to be done profitably.

Companies from other countries were interested in the same Oriental route. Being highly subsidized gave them a decided advantage. Dutch, British, Soviet and German airlines surveyed their own routes and prepared airplane specifications. Therefore competition and time entered into the picture, bringing in also United States interest. The stringent requirements narrowed the list of interested contractors to two, veterans Martin and Sikorsky. Contracts were let to the two manufacturers. Then began the enormous task of putting into material and techniques what was drawn on paper—airplanes to function dependably over an 8,000-mile watery route.

There were many technical and manufacturing problems, but a small army of highly skilled people worked them out. In October, 1931, PAA introduced the Sikorsky S-40, the first American Clipper. When it began to fly, record after record was broken for performance in the air. Engineering efforts proved out, on the whole (some had to be redone) but PAA responded by placing more such planes on requisition.

As soon as they were ready, Sikorsky’s were put on the South American route, already filled with foreign planes on busy runs. This was to be a proving ground for the grandest test of aircraft and flying man for the ultimate mission—crossing the Pacific. There they would train, test, and improve, until such flights could be done better than by anyone else.

Securing control of China National Aviation Company, Pan American sought to avoid for political reasons the arctic great circle route surveyed for the company in 1932 by Lindbergh and his wife. Trippe elected to reach the Orient by use of the springboard, Hawaii, and stepping stone islands along the route upon which to light for servicing, passengers and rest. The route was fixed as San Francisco to Honolulu, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, the Philippines, and then to China.

Shortly after Sikorsky’s plane was unveiled, the Martin craft followed. Sixteen impressive records were mercilessly broken when put to flight. Immensely pleased, Trippe and his directors knew this was the product of their efforts. A requisition was placed for expedited construction of two more such planes. Selected crews were placed on rigid training over PAA’s operating over water routes in South America and the Caribbean, covering navigation, ground school, blind flying, and every technique thought essential to the Pacific venture.

On January 1, 1935, circumstances were favorable so Trippe sent his technical staff from the east coast to San Francisco to set up a Pacific base of operations. Two months later, an expedition sailed with enough plans and equipment to construct the island facilities.

Then on April 17, 1935, the S-42 PIONEER CLIPPER skimmed to her first landing in Hawaiian waters, just 17 hours and 44 minutes from its Alameda, California, starting point. Piloted by Captain Edwin C. Musick, aboard the aircraft with him were Captain R. O. D. Sullivan, Frederick Noonan, William Jarboe and Victor Wright. The flight was a smashing success.

Then on April 17, 1935, the S-42 PIONEER CLIPPER skimmed to her first landing in Hawaiian waters, just 17 hours and 44 minutes from its Alameda, California, starting point. Piloted by Captain Edwin C. Musick, aboard the aircraft with him were Captain R. O. D. Sullivan, Frederick Noonan, William Jarboe and Victor Wright. The flight was a smashing success.

From there the survey flight crew continued to Midway, Wake and Guam. A second visit to Honolulu was made on June 13, the Clipper remaining two days before its 9 hour flight to Midway. August saw PAA’s third flight to Pearl Harbor by the hard working crew. No longer was it a stupendous spectacle.

Properly primed, the CHINA CLIPPER went on a 2,400 mile practice flight on November 2. Flying from Miami to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 8 hours and 15 minutes, the large craft turned around and flew back. One of its four engines malfunctioned slightly.

Properly primed, the CHINA CLIPPER went on a 2,400 mile practice flight on November 2. Flying from Miami to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 8 hours and 15 minutes, the large craft turned around and flew back. One of its four engines malfunctioned slightly.

Hawaii waited anxiously, expectantly. Island living continued at its normal pace.

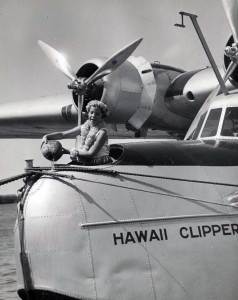

Less than eight months after construction of the airway was begun, on November 22, 1935, Postmaster General James A. Farley and Mr. Juan Trippe ordered Pilot Musick, commanding the Martin M-130 CHINA CLIPPER, to take off on the first airmail flight, by way of Hawaii and the other islands, on to its Manila destination.

Farley stated in his speech that day that this marked the beginning of “the greatest and most significant achievement in the marvelous, fascinating development of air transportation.”

Farley stated in his speech that day that this marked the beginning of “the greatest and most significant achievement in the marvelous, fascinating development of air transportation.”

Twenty thousand spectators were on hand to watch festivities at Alameda, all eyes on the immense silver airplane. They saw an estimated 110,000 pieces of mail weighing nearly two tons being stowed on board. The band struck up the tune, Star Spangled Banner, as the engines were put to the test and the big flying boat began to respond to Musick’s expert commands. Heavily but efficiently the proud plane knifed through the water.

Aboard was the veteran crew plus newcomers George King and Chan Wright. An anxious throng breathed a sigh of relief as the pride of aviation suddenly escaped from the clutching surface. As it steadily made headway over the unfinished Golden Gate Bridge, a gentleman pensively watched from the University Club in San Francisco. Emory Bronte was brought back in time eight years to the period in 1927 when his flight across the same route was made, with Ernie Smith, the first civilians to do so.

Back in Hawaii, news of the scheduled take-off was heralded with expectation, for this was the beginning of the biggest development for the Islands since the first commercial ship inaugurated its services to Hawaii many years prior. News of the CHINA CLIPPER added color to droll local events. In Miami, a second PAA clipper plane took off, departing at 6:18 a.m. for Alameda by way of Acapulco.

The huge CHINA CLIPPER was joined by a great mass of clouds, even before it left the Bay. By nightfall, the plane was completely encased by a ceiling of clouds above and below. Because this was the ninth crossing for all but two of the crew, no one was ruffled. In eight hours, 1,200 miles had been covered in the Pacific Ocean. They were in radio communication with the U.S. Coast Guard cutter ITASCA first, and then spoke to the Norwegian motor ship ROSEVILLE, followed by the USS WRIGHT 900 miles west. Throughout the night seven celestial sightings had been obtained, and 41 radio directive bearings received.

Flying at 10,300 feet, the crew sighted Molokai 200 miles away, then a great mantle of smoke from the erupting crater on the Big Island.

Triumphantly boring their way toward Diamond Head at last, Musick and his expert crew were joined by 60 planes form Oahu’s Army and Navy air forces in spectacular, sky-filling escort. (It was a fitting escort, for had not the military shown the way?).

Majestically, and once again alone, the CHINA CLIPPER ended 21 hours and 20 minutes of flying with a gentle landing on Pearl Harbor’s placid waters. The time was 10:19 a.m., the day November 23, 1935. Nosing into the floating buoy a few yards off shore from the new PAA base on the Pearl City peninsula—Pan American Airways Ocean Air Base Number One—the plane was greeted by 3,000 people who began to applaud.

Musick was an hour behind schedule because of strong headwinds for half of the journey, but otherwise the flight had been uneventful. Mrs. Stanley C. Kennedy, wife of Hawaii’s commercial aviation leader, was first to greet the flyers as they stepped onto the floating wharf. Gay festivities followed for the crew of seven. The feeling in Hawaii was most aptly put by a local newspaper, “Aloha, gallant clipper of the skies!”

Musick was an hour behind schedule because of strong headwinds for half of the journey, but otherwise the flight had been uneventful. Mrs. Stanley C. Kennedy, wife of Hawaii’s commercial aviation leader, was first to greet the flyers as they stepped onto the floating wharf. Gay festivities followed for the crew of seven. The feeling in Hawaii was most aptly put by a local newspaper, “Aloha, gallant clipper of the skies!”

Two tons of cargo went into the big holds of the CHINA CLIPPER on the morning of November 24, Sunday, in preparation for the 8,000 mile race with the sun across the Pacific with the first air mail for the Philippines and the Orient. Hand trucks brought 21 crates of fresh vegetables for PAA island air bases to the west, nine crates of oranges and lemons, 12 crates of turkeys for the first Thanksgiving dinners in the history of those colonies on Midway and Wake, and cartons of cranberries, sweet potatoes and mince meat.

Also crated were office and utility supplies, oil lamp wicks, sports equipment, electric light bulbs, spare parts, and a barber’s outfit. Also loaded were 16,000 letters (weight 265 lbs.), giving a total air mail cargo of 6,653 lbs. bound for Guam and Manila. Next came 14 passengers, two complete air base staff replacements for Midway and Wake.

Also crated were office and utility supplies, oil lamp wicks, sports equipment, electric light bulbs, spare parts, and a barber’s outfit. Also loaded were 16,000 letters (weight 265 lbs.), giving a total air mail cargo of 6,653 lbs. bound for Guam and Manila. Next came 14 passengers, two complete air base staff replacements for Midway and Wake.

At 4:50 p.m., all being ready, the crew cast off from the float. Captain Sullivan pointed the 25-ton craft’s nose into the north wind towards Midway, 1,380 miles away, as the CHINA CLIPPER became airborne at 7:05 p.m. They passed Kauai Peak, Niihau and found clear weather facing them. At this point, their course was set directly for Midway. In order, the flying boat passed over Necker Island; to the port, the French Frigate Shoals, Gardner Pinnacles, Marco Reef, then Midway, where at 2:01 p.m. (Midway time) a landing was made.

On November 25, the shortest hop (1,252 miles) was started for a tiny point on the map, Wake Island. Averaging 148.7 mph enroute, the plane settled onto Wake Lagoon after an uneventful flight.

At 7:04 p.m., November 27, the plane’s keel knifed through the waters and into the air under a 2,000-foot ceiling. At 10:21 p.m., the CHINA CLIPPER overtook the USS CHESTER, eastbound out of Manila. At 3:05 p.m. (Guam time), Guam’s Apra Harbor accepted the big seaplane. On Friday, November 29, the crew bid adieu to Guam and soon found the best weather of the journey. They climbed to 6,000 feet, much farther away from the whitecaps and ocean spray.

At 7:04 p.m., November 27, the plane’s keel knifed through the waters and into the air under a 2,000-foot ceiling. At 10:21 p.m., the CHINA CLIPPER overtook the USS CHESTER, eastbound out of Manila. At 3:05 p.m. (Guam time), Guam’s Apra Harbor accepted the big seaplane. On Friday, November 29, the crew bid adieu to Guam and soon found the best weather of the journey. They climbed to 6,000 feet, much farther away from the whitecaps and ocean spray.

As the rugged hills of the Philippines came to view, the CHINA CLIPPER’s crew, up to then too preoccupied with the innumerable tasks of the job, began to realize the significance of this achievement in American aviation. They were pleased that America’s air service, American aircraft and American personnel should be the first to accomplish scheduled air transport service over the world’s greatest ocean.

At 3:32 p.m. (Manila time), the CHINA CLIPPER came to a landing in Manila Harbor—on schedule, 59 hours and 48 minutes of flying time since leaving California.

At 3:32 p.m. (Manila time), the CHINA CLIPPER came to a landing in Manila Harbor—on schedule, 59 hours and 48 minutes of flying time since leaving California.

Thus came into reality the dreams of many over the tumultuous aviation years. For Hawaii, too, this meant the reaching of a fond dream. Millions had been invested in a venture which would produce millions in increased business. Foreseeable next was the most active water-bound aerial port in the world with huge airliners halting in Hawaii for a few hours or less enroute to the South Seas, Antipodes, and around the world.

The local press described the airplane as the newest and one of the most vital forces in the advancement of civilization. It was expected that Hawaii was to be the hub of trans-Pacific flying, military and civilian.

During this period, landing rights at Auckland were granted by the New Zealand government with PAA service to begin December 31, 1936. PAA’s attention had turned to the development of a South Pacific route to Australia and New Zealand via Kingman Reef and Pago Pago. Plans were hastened to put the new service into operation, but the lack of adequate facilities along the route forced PAA to apply for an extension of the inaugural date.

On October 21, 1936, Pan American initiated regular six-day weekly passenger service between San Francisco and Manila via Honolulu.

Captain Edwin C. Musick, in command of Pan American’s SAMOAN CLIPPER (S-42B) took off from the Division’s base at Alameda, March 17, 1937, for the first aerial survey to link the U.S., Hawaii and New Zealand. Captain Musick and his crew of eight departed from Honolulu March 23 and arrived in Auckland on the 29th of March.

A tremendous ovation came from the throngs of people who turned out to greet the pioneering Clipper and its crew. Captain Musick returned to Honolulu April 30, 1937 and on December 23, the SAMOAN CLIPPER departed from Honolulu to officially inaugurate the first scheduled cargo and mail service between the U.S. and New Zealand.

The second scheduled flight, which left Honolulu January 9, 1938, ended in the worst tragedy in the history of the Division. “Captain Musick, who had taken off from Pago Pago January 11, sent a radio message back to the ground operator –“OIL LEAK IN NUMBER FOUR ENGINE AM TURNING BACK TO PAGO PAGO MUSICK.” Another message minutes later said that the Clipper had to be lightened by jettisoning some of the fuel load. That was the last message received from the crippled plane. Later search planes found floating life jackets and an oil slick at the scene of the tragedy.

Everyone who had followed the pioneering achievements that led to the inauguration of the air route to the South Pacific felt the loss of Pan American Airways’ veteran pilot and his gallant crew. Clarence M. Young, Division Manager, summed up the deep sorrow of all Division personnel in a telegram to stations throughout the Pacific outlining a tribute to be paid the crew of the SAMOAN CLIPPER:

“All departments stop. IT IS WITH EXPRESSIBLE REGRET WE MUST CONFIRM TO YOU THE LOSS OF THE NC-34 WITH ITS ENTIRE CREW IN THE IMMEDIATE VICINITY OF AMERICAN SAMOA AT APPROXIMATELY 1930Z (11:30 A.M. PST) JANUARY 11 PRESUMABLY FROM A SUDDEN FIRE OF UNDETERMINED ORIGIN STOP CREW MEMBERS WERE CAPTAIN MUSICK COMMANDING COMMA CAPTAIN CECH. G. SELLERS FIRST OFFICER COMMA JUNIOR OFFICER PAUL BRUNK COMMA NAVIGATION OFFICER FRED MACLEAN COMMA FLIGHT ENGINEERING OFFICERS JACK BROOKS AND JOHN STRICKROD COMMA FLIGHT RADIO OPERATOR TOM FINDLEY STOP AT ELEVEN AM LOCAL TIME YOUR STATION JANUARY 17TH WEST LONGITUDE COMMA JANUARY 18TH EAST LONGITUDE COMMA PLEASE ARRANGE MEMORIAL TRIBUTE TO CAPTAIN MUSICK AND CREW BY SUSPENDING ACTIVITIES AT YOUR RESPECTIVE STATIONS TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PRACTICABLE FOR A PERIOD OF FIVE MINUTES STOP RADIO GUARD WILL BE RIGIDLY MAINTAINED ON ANY AIRCRAFT IN FLIGHT BUT ONLY COMMUNICATIONS ESSENTIAL TO SAFETY SHOULD BE SENT OR RECEIVED STOP NO PERSONS OUTSIDE OF THE COMPANY MAY BE INFORMED AND NO PUBLICITY GIVEN TO THIS PROGRAM STOP IT IS INTENDED SOLELY AS AN EFFORT ON THE PART OF THOSE OF US WHO HAVE BEEN PRIVILEGED TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH CAPTAIN MUSICK AND THE MEMBERS OF HIS CREW TO EXPRESS IN SOME MEASURE OUR DEEP SORROW AND OUR GREAT LOSS WHICH HAS BEFALLEN NOT ONLY OURSELVES BUT THE ENTIRE AIR TRANSPORTATION INDUSTRY THROUGHOUT THE WORLD STOP”

Since the Division had planned to use the Samoan Clipper on the South Pacific service, the loss of the aircraft made it impossible to continue service to Auckland.

First to make the Pacific crossings by way of Hawaii and other islands, through the years Pan American steadily increased its world services. The first Martin Clippers were augmented in 1941 by larger Boeing Clippers.

On November 16, 1945, PAA resumed commercial operations with their Boeing Clippers which had been leased to the Navy during the war. Expansion continued. On the Atlantic side, PAA and Trans World Airlines merged in 1962 to create a financially strong U.S. flag trans-Atlantic carrier (to better compete with foreign carriers which, since 1950, had reduced the U.S. share of the trans-Atlantic market from 63% to 37%).

In the Pacific during 1963, PAA inaugurated the first U.S. jet service to Tahiti. In 1964, they applied for permission to make direct flights from California to Hilo. To accommodate the expected influx of visitors, Big Islanders busily prepared accommodations. This included a jet runway, a $13 million resort area, a new airport terminal building, hotels, shops, and attractions. This direct air service is expected to increase the island’s economy, as occurred with Oahu.

At the same time, Pan American is making a bid to link the United States and Japan via Alaska, by passing Hawaii in a “modernization of the Pacific air structure.”

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.

Pan American initiated 747 service into Honolulu on March 3, 1970 with one daily 747 flight, and within a month expanded the schedule to two. In July, 1940, three additional airlines were expected to begin scheduled 747 service to Honolulu.

The 747, capable of carrying from 397 to 490 passengers, placed increased demands upon all phases of terminal facilities. The decisions of President Richard M. Nixon and the Civil Aeronautics Board meant the advent of new non-stop service from Honolulu to the Midwest and East Coast points, as well as to Anchorage, Alaska.

In rapid succession, Pan American’s 50th anniversary on November 22, 1985 of their first flight across the Pacific was followed by the announcement of the sale of their routes west of the islands to United Airlines and then the sudden closing of all operations in Hawaii on April 26, 1986.