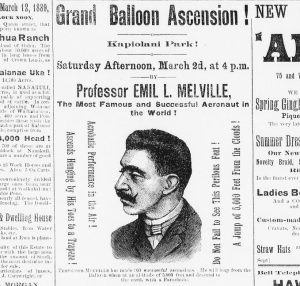

Emil L. Melville

In March, 1889, world-famous aeronaut Emil L. Melville visited Honolulu. Just prior to this visit, he had made ascension for an audience of 63,000 people at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach.

In March, 1889, world-famous aeronaut Emil L. Melville visited Honolulu. Just prior to this visit, he had made ascension for an audience of 63,000 people at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach.

The aeronaut had learned ballooning from his father, whose efforts during the Siege of Paris were of great value to France. During four balloon ascensions the elder Melville delivered 16,000 letters and messages safety across enemy lines.

Young Melville made an excellent living as a balloon demonstrator. He didn’t merely ascend, but was known for performing acrobatic stunts while airborne. Honolulu’s advertisements stated that the dare-devil would hang from a trapeze in his brand new 86-foot balloon. Daily announcements in Honolulu newspapers continued until the launch date, March 2, 1889. Hundreds of people paid 50 cents apiece and filled Kapiolani Park.

Named “America” by the aeronaut, the balloon and its associated equipment made a strange sight for Honolulu residents who had never seen a man-bearing balloon before. Positioned over the funnel of a furnace situated on the ground, the balloon’s center pole reached 10-feet in the air. Around the pole were many wrapped folds of white boat sail. A parachute was fastened to the balloon cloth. Attached to the mouth of the balloon by twine only strong enough to hold a man’s weight was the trapeze seat. To shield the balloon from Honolulu trade winds during inflation, a wooden wall was built windward of the furnace. Onlookers close to the contrivance gaped in wonder, first at the balloon and its awkward supporting apparatus, then at the man getting ready to ascend for them.

Melville and his helpers fired the furnace and with the hot gasses and smoke began inflating the balloon at 3:15 p.m. About 10-feet up, however, the balloon developed an aperture 15-feet long next to a seam. Smoke billowed out at a fast rate, so Melville pulled the balloon back to the ground, hastily sewing it up again. By the time inflation was resumed, it was five o’clock and the audience began to doubt the aeronaut’s promise to give them their money’s worth.

In spite of the sheltering wall, the now much stronger winds coming from the sea seriously hampered Melville’s efforts at inflation. Time and again, trade winds forced hot gasses back into the furnace. Finally the balloon was sufficiently inflated but then burst once again, smoke pouring out of its rents more than before. The ball of smoke and fire listed threateningly back and forth in reaction to the winds. People became panic-stricken. First the balloonist’s assistants scrambled out of the way. People in the grandstands scurried for the stairs, starting a small stampede. Carriage-drawing horses responded with terror in their eyes as they fought their harnesses. Desperately fighting the fire, Melville managed to extinguish it, but by then people had dispersed, including the King and Queen. The Royal Hawaiian Band played, but it didn’t stop the hastily departing spectators.

Embarrassed and frustrated, Melville published a letter to Honolulu’s public the following day, blaming his failure (the first he’d ever had) entirely on strong winds. He promised to give a free exhibition the following Saturday, to show his true abilities.

On March 11th, using Dowsett’s paddock at Iwilei, Melville prepared for ascent. This time, there were thousands of spectators perched atop houses, on surface craft, on nearby hills, wherever they could see . . . they expected a disaster. Inflation was started at 4 p.m. and once again trade winds deprived the balloon of its motoring gases

By 5 o’clock the contrivance began to move upward, climbing to the height of surrounding algarroba trees which, up to that stage, offered some protection from the wind. However, from the sea came strong winds. The balloon, when fully inflated was difficult to hold down. Melville stood by ready, his assistant feverishly preparing the inside. Seeing smoke rushing from two apertures in the balloon, the infuriated aeronaut grabbed hold of the trapeze with his hands and shouted, “Let go!”

Beginning to drift to one side, Melville and his balloon knocked over several people who hadn’t as yet gotten out of the way. He was dragged along by hands and feet, through a clump of algaroba trees. In the clearing, Melville sat himself atop the trapeze as the balloon drifted along almost at tree-top height. It being obvious there would be no more rise, some two or three thousand yards from the starting point the aeronaut leaped to the ground, a distance of 30 feet. Landing safely on his feet, he drew loud cheers from spectators. The balloon then rose rapidly to about 200 feet and headed peacefully, unburdened to Nuuanu Valley, where it was lost from view.

When recovered, the “America” was only slightly scorched, but the aeronaut bore deeper scars, not all of them physical. Apparently no other attempts at ballooning were made by Melville.

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.

Photo Reference

- HDNP. (n.d) Emil Melville’s Balloon Ride. Hawai’i Digital Newspaper Project. https://hdnpblog.wordpress.com/historical-articles/emil-melvilles-balloon-ride/