Inter-Island Airways/Hawaiian Airlines

Ten years had passed since Major Clark made the first over water flight in the Hawaiian Islands, followed shortly by a trio of Hs-2s going by the air route also to Molokai, Maui and Kauai. Thereafter, military craft flew in greater numbers between the islands on missions for the government and to display interisland flying capabilities to businessmen.

Charles Fern’s commercial passenger flight by civilian plane to Maui and return in February, 1920, heralded a limited capability; so did Charles Stoffer’s flight in August, 1921 between Hawaii and Oahu by way of Maui and Molokai. People were interested in the possibilities of a paying service between the major islands, but still only mildly.

Sea-going craft made the trip regularly and, although it took a great deal of travel time and the sea was rough, hauled more passengers and goods than many airplanes were then capable of doing. Besides, it was done safely.

Insofar, as public reception was concerned, successful flights across great expanses of water still only hinted of useful between-island flying possibilities. Rodgers put down at sea and was lost nine days, Smith and Bronte crashed on Molokai, and a number of lives were lost in the Dole Derby.

Although Maitland and Hegenberger, Art Goebel and Martin Jensen successfully landed in Hawaii, theirs and the other aircraft carried only two people. Kingsford Smith’s Fokker could haul four people without mishap from California to Australia; therefore it had a positive capability. The time was right.

Ed Lewis with his chief pilot, Martin Jensen, made overtures for the service. On July 1, 1929, a steamship line moved decisively to provide interisland flying. The Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company, Ltd., of Honolulu, announced that Charles H. Dolan II was hired to investigate possibilities of commercial flying between the major islands of the group.

Two visiting airline representatives soon returned to the mainland and it looked like “competition” would be local, Ed Lewis and the steamship company. Charles Stoffer was not in contention. “I believe I had two strikes against me due to my former participation in stunt flying and purposely crashing planes for motion pictures, which was certainly a reasonable objection as I review my efforts in that period,” Stoffer said in 1965.

In January, 1929, Lewis gave way to his powerful competitor, saying, “There’s no room for two such companies.” Under the leadership of World War I Navy pilot, Stanley C. Kennedy, president and manager of the steamship company, Inter-Island Airways, Ltd., was formed.

Young Kennedy had visions of flying for many years. The native of Oahu was mildly interested when Bud Mars first penetrated Hawaiian skies in the SKYLARK in 1910. A few months later, he was enticed from his breakfast table by the strange beating sounds of Didier Masson’s monoplane clumsily flying overhead from Leilehua to Kapiolani Park. Daredevil antics by Tom Gunn and his flying boat kept alive within the young man a desire to eventually take to the air. But it was not until the Great War that Stanley Kennedy was to pilot an airplane. Dissatisfied with a Washington desk job, the naval officer talked his way into flight training in Pensacola, Florida. In short order, Ensign Kennedy sported wings as Naval Aviator No. 302.

Clamoring for battle, he pounded desktops with success. In January, 1918 he went overseas where he was glad to fly a plane other than the N-9 (Jenny) trainer, the H-16 flying boat. He made patrol missions from Killingholme, on the east coast of England near the mouth of the Humber. (It was one of the most powerful air stations in Europe, with 50 planes and some 2,000 men.)

At war’s end, Kennedy returned to Honolulu where his father was president of Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company, Ltd. Enthusiastic utterances about aviation became Kennedy’s trademark. Visions of the possibilities of commercial flying between the islands, while patrolling North Sea waters, returned to mind and one day the aviation enthusiast decided to advance his idea.

“Dad, you’re going to have to look into aviation and get into it,” he told the elder Kennedy. “Our business is transportation. Aviation is transportation just as much as steamers. It’s the coming thing.”

“My father would have none of that kind of talk,” Kennedy said. ‘I knew aircraft were limited, of course. Engines were unreliable, planes were expensive to buy and maintain, and the payload to be carried was limited. But it was only a matter of time before aircraft would go into service, and I thought the company should be the first.”

Kennedy continued, “It was little use with Dad, even though the Army made interisland flights regularly. He told me to get my feet on the ground. ‘You were up in the air too much, and you’re still there,’ he said, then predicted, ‘I’ll never see such a thing in my lifetime, nor will you.’ Dad died in 1926, three years too soon to see it come about, spearheaded by our company, as we had done with steamer travel between the islands.”

Kennedy continued the chant for a flying service. A few years later, becoming manager of the parent company, he found more listeners because of his position. Lindbergh’s dramatic flight in 1927, followed by that of Maitland and Hegenberger, did much to convince officers and directors of this company of the possibilities of air travel.

Further encouragement was provided by the Hawaii legislature which, with the hope of fostering interest in aviation, passed a resolution exempting any potential interisland airline from taxation for five years. Kennedy and company moved fast to become the first and biggest interisland commercial flying enterprise. Kennedy’s aviation knowledge and experience proved invaluable, as the company exploded with activity to compete for and inaugurate the service.

Remembering the difficulties and tragedies involving the California to Hawaii pioneers, Kennedy was primarily concerned with flight safety. He squirmed at the thought of one of his airplanes having to land in the water, as Rodgers had done; barely make landfall, as with Smith and Bronte; get lost in the sea, as the MISS DORAN and other races had experienced.

It was hard for him to visualize a land plane of any type flying his routes. Concentrating on safety, speed, and comfort of passengers, Kennedy worked hard to get what he felt was the right type of airplane, pilots and equipment to start the new company. Kennedy personally visited factories under consideration, and flew and closely inspected a number of craft.

Finally one pleased him, the Sikorsky Amphibian S-38. It passed all tests so an order was placed. The S-38s had the capability of operating from either land or water. Each of the two engines developed 420 horsepower. The plane climbed well. Top speed was 125 mph, cruising at 110. Pan American Airways used similar planes for flights in Central America, therefore providing worthy examples.

Finally one pleased him, the Sikorsky Amphibian S-38. It passed all tests so an order was placed. The S-38s had the capability of operating from either land or water. Each of the two engines developed 420 horsepower. The plane climbed well. Top speed was 125 mph, cruising at 110. Pan American Airways used similar planes for flights in Central America, therefore providing worthy examples.

Kennedy knew that flying between the islands would present another difficulty not found on the continent, where navigational aids were abundant, and fields plenty. Airlines there were helped by having an airmail subsidy with the United States government (for which Hawaii was to wait five years). Hawaii lacked many assets for successful airline operations; there was much to be done.

Some company people were dubious to the end, but not so much as the public who were to comprise the passengers. Flying over water was a dim prospect for Islanders. “We had to give people the feel of flying, first” Kennedy says, “so they could see it was safe as well as fun; give them an aerial view of the Island, and just generally get them used to flying in a plane. The company bought a Ballanca and put it to use for this purpose. Of course, the people liked it. Word spread, soon flying lost its taboo feature and the public became ready for the service.”

Some company people were dubious to the end, but not so much as the public who were to comprise the passengers. Flying over water was a dim prospect for Islanders. “We had to give people the feel of flying, first” Kennedy says, “so they could see it was safe as well as fun; give them an aerial view of the Island, and just generally get them used to flying in a plane. The company bought a Ballanca and put it to use for this purpose. Of course, the people liked it. Word spread, soon flying lost its taboo feature and the public became ready for the service.”

In May 1929, from the mainland came an announcement that the Hawaiian Airways Company, Ltd. was incorporated under the laws of Nevada for a proposed interisland service. Officials planned to inaugurate the service within a month (five months earlier than Kennedy’s firm), if they received early delivery of two Fokker land planes.

An improved version of the BIRD OF PARADISE and SOUTHERN CROSS, the new company’s Fokker F-10 Super-Tri-motors would carry two pilots, 12 passengers, baggage and freight. The wing span was 79 feet 3 inches, length 50 feet, top speed of 145 miles per hour, cruising at 125. The firm’s plans for construction of hangars and other facilities were not complete but the planes were expected to fly from Oahu to Hanapepe Field on Kauai (courtesy of the Army), then the Waiakea Airport at Hilo.

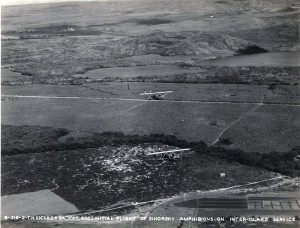

Kennedy continued preparations and on November 11, 1929, Inter-Island Airways’ first two Sikorsky amphibians took to the air, inaugurating the new service. Just two years previously, the airport had been given its new name, John Rodgers, after the pioneer flyer.

Inter-Island’s inaugural ceremony was attended by Honolulu’s officialdom, with the Governor’s daughter assisting in christening the airplanes, HAWAII and MAUI. Governor Judd addressed the assemblage.

The two planes took off at 9:30 a.m. for Hilo, Hawaii, to touch Maalaea Field, Maui, on the way. Once airborne, they were joined by 22 Army and 27 Navy aircraft from Wheeler and Luke Fields. When they reached Diamond Head, all but six flying escorts left the S-38s and returned to their bases. Three hours later, a large assemblage of people greeted the landing planes at Hilo.

The pilots, Carl Cover and Charles I. “Sam” Elliott, carried 13 passengers on the first trip. Then at 3:10 p.m., they took off from Hilo with more passengers and touched Maui en route, returning to John Rodgers Airport at 5 p.m. Thus the service was finally placed into operation after many years of talk and attempts, spanning the connecting island waters by aircraft. The Hawaiian Islands were now molded into one massive territory by a faster mode of transportation, as had been done by surface craft many years previously.

The route flown by Inter-Island had originally been established for airmail flying. Operating without an airmail contract, however, proved financially burdensome. The company lost money each year and at the height of the Depression only 6,600 passengers were carried.

The route flown by Inter-Island had originally been established for airmail flying. Operating without an airmail contract, however, proved financially burdensome. The company lost money each year and at the height of the Depression only 6,600 passengers were carried.

“Being a subsidiary of the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company, which was solvent, we could absorb the loss until the airmail contract came through,” Kennedy stated. Strong emphasis was placed by Hawaii on obtaining the subsidy, and on October 8, 1934 the first official U.S. airmail flight in Hawaii was made from John Rodgers Airport.

As a result, flight schedules were speeded up; two Sikorsky S-43 16-passenger planes were purchased (and flown for the first time in December 1935). The “Baby Clippers” were powerful enough to take off from the water on one engine; their top speed was 200 mph at 7,000 feet altitude, cruising at about 185 mph. Improved passenger comfort and safety features were provided, such as shatter-proof and sound-proof glass, indirect controlled ventilation, and a large lavatory. The service continued its pattern of growth through the years.

As a result, flight schedules were speeded up; two Sikorsky S-43 16-passenger planes were purchased (and flown for the first time in December 1935). The “Baby Clippers” were powerful enough to take off from the water on one engine; their top speed was 200 mph at 7,000 feet altitude, cruising at about 185 mph. Improved passenger comfort and safety features were provided, such as shatter-proof and sound-proof glass, indirect controlled ventilation, and a large lavatory. The service continued its pattern of growth through the years.

“Hawaiian Airways went into operation shortly after we did,” Kennedy recalled, “but didn’t last too long. One day their Kreutzer plane made a forced landing in Kohala, Hawaii, with a Hawaii legislator aboard. People wouldn’t fly with them after that. Even the pilot resigned, coming to work for us.”

By 1936 there was a drastic upsurge in local passenger traffic and it became apparent that Inter-Island Airways’ Stanley Kennedy was correct in his predictions and hopes. After seven years of scheduled service without an accident, the traditionally boat-minded islanders realized the safety of interisland air travel.

Riding on the crest of this upsurge, the company bought two Sikorsky S-43 amphibians which carried 16 passengers and a crew of two (twice the capacity of the S-38). At 7,000 feet altitude the new plane could cruise at 185 mph. It could take off with one engine, had unimpaired vision (one wing instead of two), shatter-proof, sound-proof glass, and numerous other attractive features.

In the next three years, two additional S-43s were put into service. The company’s fleet then consisted of four S-43s which were used on scheduled service between Honolulu, Maui and Hawaii as well as between Honolulu and Kauai, and two S-38s for services to airports on the other islands where inadequate facilities did not permit the use of the larger S-43s.

The S38s were also used for charter and emergency services as the occasion demanded. Success in attracting passengers to the amphibians was due in large measure to the fact that they could safely operate from land or water.

During the war years, the airplane was the only means of interisland transportation and Hawaiian Airlines boomed as thousands of people took to the air. However, United States control established by the military in Hawaii resulted in seats being allocated on a strict priority basis to passengers directly connected with the war effort. This system of control had its damaging effects on HAL immediately after the war, because islanders sometimes resented the military system of priorities. The way was clear for a second interisland service to be established.

During the war years, the airplane was the only means of interisland transportation and Hawaiian Airlines boomed as thousands of people took to the air. However, United States control established by the military in Hawaii resulted in seats being allocated on a strict priority basis to passengers directly connected with the war effort. This system of control had its damaging effects on HAL immediately after the war, because islanders sometimes resented the military system of priorities. The way was clear for a second interisland service to be established.

Hawaiian Airlines continued to serve interisland needs. On its 23rd anniversary, HAL acquired five new Convair 340s, the first pressurized aircraft in interisland operation. Pioneer Stanley Kennedy retired from active management of the company in 1955, becoming Chairman of the Board.

Under Arthur D. Lewis, former Vice-President of American Airlines, the company was completely reorganized to withstand better the effect of increasing competition and to prepare for expansion. The Convair’s seating capacity was increased by six. Four of the six DC-3s were converted for aerial sightseeing, provided with panoramic windows five feet in length and an increase in seating by three (from 28 to 31).

Shortly, HAL’s service included twice-weekly service form Honolulu to Midway Island, carrying 72 tons of cargo and passengers per month in contract with the Military Air Transport Service. Hawaiian Airlines next began seeking a trans-Pacific jet service.

During 1963, HAL carried 2,105,046 ton-miles of air freight delivering newspapers, laundry, household goods, eggs, chickens, perishable foods, and U.S. mail between the islands.

November 11, 1964 marked 35 years of operation as a scheduled interisland air transportation company, claiming the distinction of being one of the oldest scheduled air carriers in the United States and holder of the world’s safety record (carried throughout this period were eight million passengers without a single fatality to either passenger or crew member, and traveled over 1.2 million passenger miles).

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.