December 7, 1941

The Attack on Pearl Harbor

One of the Hawaiian Department’s new mobile radar “listening posts” was situated atop Kahuku Point on Oahu’s northernmost tip, called Opana. It had been in operation only two weeks, manned by the 515th Army Aircraft Warning Service. The key item of equipment was the SCR-270B Radio Direction Finder, a primitive form of radar. According to its operators, the oscilloscope at Opana offered the clearest picture of all six Oahu units. Two men had been on duty in the trailer since noon of December 6, off and on. Having started at 4 a.m., the men on duty were scheduled to go off shift at 7 a.m., the same time as the others. They were Private George E. Elliott Jr., who functioned as plotter and Private (3rd Class Specialist) Joseph L. Lockard, operator. It would have been interesting to them had the B-17s come from the mainland, because they would have caused a large blip on the scope; but the tour of duty had been dull and uneventful.

At 7 a.m., Lockard and Elliott decided not to go home right at quitting time, feeling it would be a good opportunity for Elliot to operate the set for awhile. Being new in the line of work, the training would be useful to him and to the organization. Elliott was eager to get into the operator’s seat. It was only two minutes after seven o’clock when ”something out of the ordinary” appeared to him on the screen. Lockard also saw it, looking over the other’s shoulders. Puzzled, the operator plunked into his regular position, for he had never before seen such a large blip. There were two blips, at close inspection. Lockard suspected a faulty set and began setting adjustments. At this he became convinced what he was seeing was the radar echo of two large groups of airplanes.

Elliott rushed back to his aircraft warning plotting board and in less than a minute determined the blips to be at three degrees east or north and 137 miles north of Opana.

Elliott suggested the Information Center at Fort Shafter should be told of the findings. Lockard, at first unsure, allowed Elliott to place a telephone call. This was seven minutes after the blip first appeared. Raising only the male telephone operator to whom he revealed the unusual blip, the anxious soldier was told nobody was available. The operator called back a few moments later, with Lieutenant Kermit A. Tyler on the line. A new assignee, on the 4-8 a.m. shift as pursuit officer, the young officer talked with Lockard about the matter then speculated the blips depicted B-17s from Hamilton or Navy planes on patrol duty. Told to forget about it, for at least the next 30 minutes the two men nevertheless continued to plot what they saw as a “fine problem.” Then they made off to deliver the unique overlaid map to superiors and partake of a meal. At this point, the on-going Japanese warplanes were about 30 miles from Oahu, soon to fade from the scope due to a back wave from the mountains.

ATTACK!

Now over Kahuku Point, Commander Fuchida fired his flare pistol and propelled a “black dragon” into the sky. His position as aerial commander was made clear by the distinctive red and yellow strip around his plane’s tail. This was the order to attack. As pre-arranged, at this signal the 183 planes of the first wave broke formation. Dive bombers headed upward for the 12,000 foot mark, horizontal bombers to 3,500 and torpedo bombers plunged to sea level then into mountain passes to avoid detection as they headed for Honolulu military targets. A second flare confused the attackers, who nonetheless formed a cloud of fire power on a deadly mission.

The second wave had taken off 45 minutes after the leading element. Consisting of 50 horizontal bombers, 80 dive bombers and 40 fighters, they varied course on signal and made for their targets.

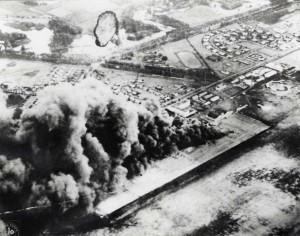

At 7:55 a.m. the first Japanese planes were seen southeast of Hickam Field, fighters soon joined by 28 bombers. They made three separate attacks in a savage 10-minute assault on the flight line, shops and buildings. Seven fighters later strafed aircraft taxiing on the field for defense after a lull of 15 minutes, then pounded the base a third time at 9 a.m. In all, Hickam suffered 42 planes totally destroyed and many more damaged extensively.

Marine Air Group 21 at Ewa, located adjacent to Pearl Harbor, was hit. Situated there, also wing-tip to wing-tip per instructions, were 11 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters (the newest of USMC fighter planes), 32 Scout dive bombers and six utility planes. Breaking the sabbatical calm, the approaching roar of strange airplanes, enticed the Officer of the Day away from his breakfast. He stepped out to see hordes of airplanes in the sky. Looking at his watch, he read 7:55 a.m. As the craft drew closer he made the planes out to be Japanese and sprinted toward the guard house to sound the alarm. They came in low over the mountains, skimming smoothly past Barber’s Point and, at 7:57, swooped down on the base with blazing armaments. There was no chance, and now no need, for sounding the alarm. Flying as low as 20 feet from the ground, 21 “Zekes” spewed armor piercing shells into the airplanes on the flight line. Pass after pass was made, during the 30-minute attack. Marines rushed out and valiantly began firing at the warplanes with the red-insignias, armed only with rifles and pistols. Destroyed were nine Wildcats, 18 Scouts and all but one utility plane. A second wave of “Zekes” was followed by “Vals” which had joined the first group about 15 minutes after the attack began, concentrating on buildings, installations, hospital tents and personnel. The third attack was by 15 “Zekes.” But this time, Marines had put into action some spare machine guns. Joining them were ground crewmen manning rear-cockpit guns in some of the riddled dive-bombers. They shot down one fighter plane, and damaged several others. Four Marines were killed, 33 of their planes devastated and 16 left too badly damaged to fly.

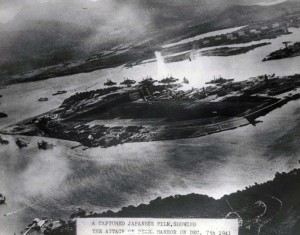

At one minute after 8, Pearl Harbor and Ford Island were overrun by attacking planes. Japanese bombers destroyed 33 of the 70 planes on Ford Island. Seconds later, dive bombers and torpedo planes struck at warships in the harbor on a sustained basis. Within 30 minutes, torpedo planes made four attacks, dive bombers eight; and after a 15-minute lull, another half hour of vicious bombing and torpedo attacks was started, finally ending at 9:45 a.m. Most of the attacking planes approached Pearl Harbor from the south. Some came from the north over the Koolau Range, where they had been hidden en route by large cumulus clouds. The Pacific Fleet’s in-place 94 vessels were pummeled. Most heavily hit was the battleship force. Within a short span of time, all seven battleships had been hit at least once.

The ARIZONA took five hits with large armor-piercing bombs and sank in less than nine minutes. CALIFORNIA and WEST VIRGINIA had been sunk, the OKLAHOMA capsized with four shells in her hull, the NEVADA was severely damaged and beached to prevent sinking; the TENNESSEE received additional damage, as did the PENNSYLVANIA. In all, six ships were sunk, 12 considerably damaged, others suffered minor hits. Naval facilities had been seriously damaged, others suffered minor hits. Fortunately, at the time of the attack the Pacific Fleet’s carrier force was not in Pearl Harbor. The SARATOGA, just out of overhaul, was moored at San Diego. The LEXINGTON was at sea about 425 miles southeast of Midway toward which she was headed to deliver a Marine Scout Bombing Squadron. The ENTERPRISE was also at sea about 200 miles west of Pearl Harbor, returning from Wake Island after delivering a Marine Fighter Squadron there.

Wheeler Field’s turf now held wartime planes, P-26, P-36 and liquid-engine P-40s, where pioneer aircraft once tread. Of the flock, six planes from the 47th Pursuit Squadron (P-36s and P-40s) were positioned at Haleiwa. The 44th Pursuit Squadron was also away, at little Bellows Field on the opposite side of the island. Rows of planes were neatly lined up on Wheeler’s wide cement apron, wing-tips practically touching one another. On alert for days with guns loaded, this Sunday morning they were without ammunition, cleaned up for the weekend to prevent mishap. Four-hour alerts prevailed, plenty of time to install armor piercing shells and tracers before heading off to help the Philippine protectors, if needed.

FIGHTER PILOTS RESPOND

Of the many from Wheeler who were to perform heroically, there and later in Air Force careers, Lieutenants George S. Welch, Kenneth A. Taylor, and a quite new second lieutenant by the name of Francis S. Gabreski, stand out.

Welch and Taylor, on the early morning of December 7, had begun to feel sleepy after being awake all night. The Wheeler Officers’ Club dance was enjoyable, but an ensuing poker game dragged through the entire night. Swimming was excellent at Haleiwa, where their planes were, but the Bachelor Officers Quarters beds sounded more appealing to the tired pair. Gabreski had been out, too. He was at nearby Schofield Barracks’ Officers’ Club, dining and dancing with an attractive young lady visiting her Schofield-based uncle. He was back in his BOQ, a two story wooden building located next to the permanent housing area near the main gate, just rolling over in bed from a deep sleep. Looking at his watch, Gabreski saw it wasn’t yet 8 a.m., and immediately thought about getting up to go to church. He rolled over lazily for another few moments, but then a whining noise followed by a terrific explosion gave him a start. Recalling the incident, Gabreski said: “At first I thought it was one of the Navy patrol planes on maneuvers; but then there was another hit, this time pretty close. I heard an airplane flying over the rooftops so I ran out to look. I just barely caught a glimpse of a big red circle on the plane. The rear gunner was spraying the buildings with bullets.”

At that, Gabreski ran up and down the BOQ hall alerting everyone to the fact they were being bombed and strafed. Rushing to the front door, he and some of the other pilots looked toward the flight line. “It dawned on me and the other dumb-founded men,” Gabreski went on, “that this was an actual bombing and our airplanes and hangars were being hit. Our second thought was, what we could do to help save the planes.”

In follow-the-leader fashion, approximately 25 Japanese dive bombers came onto the field from about 5,000 feet altitude, unloading their bombs on the exposed rows of airplanes. The attacked lasted 15 minutes.

Welch and Taylor, back in the club, also had the idea the Navy was out on maneuvers until they saw live bombs being dropped, explosions and fire. Running up to the closest telephone, Welch placed a rush call to Haleiwa where the outfit’s P-40s were sitting unarmed. The reply was long in coming, but when someone answered he was promptly directed to load several of the P-40s, particular “mine and Taylor’s.” Then five officers hopped into vehicles and sped for the airfield 10 miles away. They were Lieutenants Harry M. Brown, Robert J. Rogers, John J. Webster, Welch and Taylor. Crewmen worked fast putting in ammunition and carrying out last minute servicing. The pilots raced down the winding road past pineapple and sugar plantations for the normally placid beach playgrounds of Haleiwa.

In the meantime, Gabreski and his mates looked out across the sky for signs of more enemy aircraft. “Suddenly out of nowhere four planes came through Kolekole Pass and leveled out to strafe the flight line. They set up more fires. We got a good look at what was going on and identified the attackers as Japanese. We decided to rush down and try to salvage what planes we could. Only partly dressed, we ran toward the flight line when a couple of pursuits came down on us with blazing guns. We hit the dirt until they’d passed over, got to the line and physically began pushing and shoving planes away from burning aircraft and buildings. Altogether, we managed to salvage about 30 planes. One hangar that was set afire held 30-caliber ammunition. Inside the heat was so intense that cartridges exploded, sending tracers around men and planes. The last hangar held all the refueling trucks, completely filled with gasoline. We tried to move them but found no keys. So we had to leave them to the mercy of whatever set them off first, planes or fire.”

Arriving at Haleiwa’s flight line, the five pilots climbed into their pursuits after checking to make sure they were armed. Without knowledge of type or number of attacking enemy planes, they proceeded on their own initiative against the heat of the attack, in the vicinity of Barber’s Point. They were airborne by 8:15 a.m. Welch and Taylor observed a formation of 12 planes over Ewa, about 1,000 feet below and 10 miles away. The two paired off. Beginning to fire at one of the enemy, Welch discovered one of his guns had become jammed. Quickly, he pulled into the clearing above the clouds, checked his craft then returned to the scene of action over Barber’s Point. Seeing a Japanese plane heading for the sea, he pursued and shot at it until it fell into the ocean. Taylor shot down two planes. No more in sight, the pair proceeded to Wheeler Field for fueling, more ammunition and back into battle. Arriving at home base, Welch laughed at his uniform. He was still wearing Tuxedo trousers. Lieutenant Brown, caught amongst a host of enemy planes, began to shoot his way out. He sent one plane careening into the ocean just off Kahuku Point.

Four P-40s and two P-36s got off from Wheeler 35 minutes after the initial attack and during the next hour flew 25 sorties.

While Taylor and Welch watched their planes being refueled and the one gun cleared, another wave of planes came in from a low altitude. Three headed straight for Welch, who managed to take off before being hit. Taylor got off, too. A chandelle maneuver permitted him to escape the accumulated force of eight to 10 planes. One got on his tail but Welch out-turned him and, his guns blazing at the pursuer, sent him to a fiery death between Wahiawa and Haleiwa. His plane was hit, but Welch headed for Ewa where he saw another plane heading for the open sea. He shot it down about five miles off shore, and then returned to Haleiwa. All told, Welch claimed four planes, Taylor two with two probables (later confirmed), and Brown one. Lieutenant John L. Dains used both a P-36 and P-40 in sorties but was shot down by anti-aircraft fire from Schofield Barracks. Haleiwa gave the enemy the most resistance that day and was neglected entirely by Japanese bombers and strafers because it was not on their maps.

Bellows Field received light damage. At about 8:30 a.m. one pursuit strafed the tents then nine more arrived to attack the flight line. Preparing to take off in armed P-40s assigned to the 44th Pursuit Squadron were Lieutenants Hans C. Christensen, George A. Whiteman, and Samuel W. Bishop. Christensen was killed climbing into his airplane. Whiteman and Bishop managed to get airborne. Whiteman barely cleared the runway when he was shot down. Bishop’s P-40 was attacked, sending it crashing into the sea. Bullet in leg, Bishop swam to shore. At 8:50 a.m., four P-36s from the 46th Pursuit Squadron left Wheeler to give Bellows a hand. Included in this group were Lieutenants Philip M. Rasmussen, Lewis M. Sanders and Gordon H. Sterling. Greatly outnumbered, they nonetheless attacked the nine planes. Rasmussen shot an enemy from the sky, so did Sanders. Sterling was downed. All together, five people from Bellows were killed and nine injured.

Close to 12 o’clock noon, Wheeler’s 45th Fighter Squadron was ordered into the air. Gabreski and 11 other pilots got airborne in a mixture of P-36s and P-40s heading for Pearl Harbor where they were to receive further instructions upon arrival. “One objective of the exercise, it turned out, was to look for a carrier. But we couldn’t do anything until we received orders in the air,” Gabreski explained. “We never got them. Arriving over Pearl, we were shocked by gunfire from the ground, both from Hickam and Pearl Harbor. We were flying about 5,000 feet altitude and none of us were hit, but seeing the explosions from confused Americans below us, we broke formation and headed for home. One officer, Lieutenant Fred Shifflet, dove his P-40 down to make an identification pass over Hickam so they could see we were not Japanese. He received a heavy volley of fire from many directions, was hit profusely but not knocked down. Recovering, he made tracks for Wheeler and just managed to land when his engines froze up. The plane was full of holes, but Fred climbed out unhurt.” Wheeler lost 42 combat planes, and others were damaged. Army planes made a total of 81 take-offs that day.

NAVY PLANES

During the attack, 25 Navy planes were in the air. Included in this total were three PBYs from Patrol 14 of Patwing 2 carrying live depth charges. They were under orders to sink any submerged submarines unescorted and outside the submarine sanctuary, four more PBYs cooperating in training exercises off Kaneohe, seven Midway-stationed PBYs, and, from Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s Task Force 8, (launched off the ENTERPRISE 200 miles west of Pearl Harbor) 18 scout bombers with instructions to scout a distance of 150 miles and proceed to Ewa Marine Base. Unaware what was taking place, they inadvertently joined the fight but were armed and so could be useful. About half were lost in battle; one fled to the island of Kauai and the remaining managed to land on Oahu. Thereafter, no Navy planes were to get into the air.

In the midst of the attack, from Hamilton Field came 11 B-17s belonging to the 38th and 88thReconnaissance Squadrons, on the first leg of their flight to the Philippines. Surprised by heavy pursuit attack, the large bombers were forced to take evasive action and seek a landing place. Two came in at Haleiwa, two at Wheeler, and one on a golf course at Kahuku. The rest landed at Hickam; one was destroyed in the process and three badly damaged.

KANEOHE NAS

Kaneohe Naval Air Station was strafed twice and then bombed 25 minutes later. Twenty-seven of the 33 planes on base were destroyed and six damaged. (Three were on patrol at the time.) One hangar was burned to the ground, another severely damaged.

CIVILIAN AIRPORT

At Honolulu’s John Rodgers Airport, a Douglas DC-3 operated by Hawaiian Airlines was preparing to admit passengers for a regular inter-island flight. Suddenly, from out of the sky came a Japanese pursuit plane, guns blazing. The time was 7:55 a.m. Robert Tyce, pilot of the K-5 Flying Service, was struck in the head by a machine gun bullet and killed, but no one else was hurt. No bombs were dropped on the airport, all damage being caused by aircraft cannon and machine gun fire. Shot at in the air around the field was a privately owned Aeronca. Another Aeronca, with Oahu legislator Roy Vitousek at the controls, was pursued and shot at by two Japanese planes near Kahuku Point, as the task force headed for Pearl Harbor. Both planes came down safely but with confused pilots and passengers. Marguerite Gambo was flying with a student on a cross-country trip at the time. Seeing what was occurring, she went through a seldom-used pass and landed safely. Four Gambo planes were in the air that day, two failed to return.

AN ENEMY ON NIIHAU

The air war extended to Niihau, another Hawaiian island on December 7, 1941. One Japanese plane departing the battle arena came to land on the tiny island of Niihau. Except for two Japanese employees, Niihau’s residents were all Hawaiians. The island was privately owned (still is) by the Robinson family, dating back to when King Kamehameha IV persuaded Elizabeth Sinclair to purchase and occupy it. Niihau had no communication with the other islands, except by boat or ship, therefore residents had no knowledge Oahu was being attacked.

The bullet-riddled plane was one of two which had flown overhead earlier, sighted by Island residents just before going into church for their forenoon services. The planes headed down the Niihau coast in the general direction of Kaula rock. One was smoking badly and seemed to be in difficulty. They were recognized as Japanese. Shortly after church services were over, one was seen coming in low. It crash landed on the heavily furrowed and rocky field, coming to a sudden stop near the house of Hawila Kaleohano. (For a number of years, acting on military request, Niihau Ranch kept all flat lands unusable in this manner for just such a purpose). The plane was considerably damaged. When Hawila came up to the plane he found the Japanese pilot reaching for his pistol and snatched it away from him. The Hawaiian also confiscated a map of Oahu and other papers inside the man’s shirt. Unable to understand what the pilot said, Hawila sent for the Japanese residents In the ensuing conversation, the local employee, Harada, ostensibly could extract no information which hinted of the attack, nor the flyer’s affiliation with it. Recognizing the Japanese insignia on the plane, some of the people suspected the truth. The group assembled around the strange sight agreed it would be best to guard the intruder until Mr. Robinson returned from his visit to Kauai A double guard system was set up for the man and his airplane Four days went by, Kauai’s military authorities held up Robinson’s departure clearance until the Oahu attack situation was somewhat stabilized Harada, one of the pilot’s guards, talked villagers into allowing the stranger to move into his quarter to appease the worried people—still under double guard. Several days later, the pilot admitted participating in the raid on Oahu, explaining that he and the other pilot sighted were heading for their supposed carrier location somewhere north or northwest of Kauai. Unable to find it, they made for the alternate position southwest of Kaula, also without success. It was near Kaula that the other plane crashed into the sea, whereupon the companion flew to Niihau. The man expressed a willingness to remain on the beautiful island after the war. Later he boasted that Oahu’s defenses had been demolished.

On Friday, Harada stole a shotgun from his employer’s household. He armed the pilot then they shut up the other guard long enough to escape. Then they set out in armed search for Hawila, the coveted papers and map. The other Japanese resident, Shintani (a Robinson employee of long standing), was sent after Hawila with an offer of a large payment of money for the papers. The Hawaiian refused. At this point, Shintani joined the Hawaiians and had nothing more to do with the pilot. After Shintani’s visit, Hawila saw the pilot and Harada heading his way. He alerted the villagers and then joined a group of people preparing to go by boat for help. The people moved their families out of harm’s way.

Unable to find the elusive Hawaiian, the pair removed one of the plane’s guns and took it along to force cooperation from villagers. Friday night, the pistol and map were uncovered in Hawila’s house but not the papers or the man. Infuriated, they proceeded to burn down the house and set fire to the plane. Then the search continued. People captured were uncooperative.

In the meantime, Benehakaka Kanahele and his cousin, Kaahakila Kalimahuluhulu, confiscated the machine gun’s ammunition. They carried it off boldly, with the Japanese only a short distance off. Several men rowed away in a whale boat for Kauai. Included in the party were boat captain Kekuhina Kaohelaulii and Hawila Kaleohano.

Upon receiving word of the incident, Robinson notified the military. Army Lieutenant Jack Mizuha, a squad of infantrymen, and the Niihau party, sped for Niihau aboard the lighthouse tender, KUKUI. When they put in to shore, one week after the attack, the need for them had been eliminated. Saturday morning, Kanahele and his wife were captured. Sending the Hawaiian in search of Hawila, the Japanese held the wife as hostage. Concerned with her safety, Kanahele returned and waited for an opportunity to disarm the two men.

The couple were forced to walk back to the village at gunpoint. The desperate men announced their intention to kill Kanahele and his wife as an example, and continue killing until the vital papers were revealed. The Hawaiian saw an opportunity and quickly attacked the pilot. His wife was seized by Harada. The Hawaiian barked out orders not to harm her, as he struggled with the armed man. Suddenly, three bullets were pumped into Kanahele’s body from the pilot’s pistol. The bleeding Hawila, however, picked up the startled invader and smashed his head against a stone wall. The blow killed him. Seeing this, Harada made use of the shotgun as a suicide weapon.

In a statement to Mr. Robinson later, Kanahele said he was sorry to have to kill the flyer. Being shot and bleeding freely he was unsure how long he would be useful to his wife, children and the others on his beloved Niihau. The brave Hawaiian survived and was later cited by the President of the United States.

Niihau went on to serve the war effort. In the early stages, it was only a station for telephone communication with Kauai. Later, material from sunken ships, such as gasoline and oil that drifted in, was collected and turned over to the Army on Kauai. Army supplies and personnel were moved about by the Ranch’s sampan. Navy ships were given help whenever they landed. Later in the war, the Coast Guard established a station on the island after the Army discontinued its post. Much beef and mutton were supplied to Kauai; wool and honey as well.

SUMMARY OF DAMAGES

From the first wave attack, 29 Japanese planes failed to report back to their carriers. Then a roughened sea caused about 50 planes to smash on carrier landings.

Of the 169 Naval aircraft on Oahu, 87 had been destroyed. Only 79 out of 231 Army planes remained flyable. At Hickam, 163 people were killed, 43 missing and 336 wounded. All told, the December 7 disaster resulted in a loss to the Untied States of 2,008 Navy men and 109 Marines (more than half of which are entombed in the USS ARIZONA), and 218 Army personnel. On the injured list were 710 from the Navy, 69 Marines, and 364 soldiers. The total casualty rate was 3,478. For Japan, less than 100 men were lost. Outright, the United States lost 188 planes, Japan 29 plus 50 damaged. The U.S. suffered severe damage to 18 ships and minor damage to a number of others; Japan lost one full-size submarine and five midget submarines.

ONE MAN’S STORY

The story of all the tragedies emanating from this momentous “day of infamy” has been told many times, and continues to be explored. Written in history is the performance of free peoples everywhere in reaction to a dastardly deed by a misled nation. The men and women who survived the attack, and others who felt its effects, went on to varying degrees of contribution to the war effort, later to a short period of peaceful preparation, followed by an international conflict in Korea. The subsequent deeds of one man in combat are noteworthy.

Second Lieutenant Gabreski was confused and dazed, as were other men, when Army airplanes were being torn to blazing shreds during the most effective—but awakening—attack against the United States in history. Acting as a modern Paul Revere, later under fire he helped safeguard planes from fiery devastation. Not until the attackers were gone did he get into position of possible engagement with the enemy, the job for which he was trained and dedicated; then he was shot at by members of his own forces, made to go quietly back to home base. There was an unanswered question in his mind. He felt great admiration, and probably even envy for Welch and Taylor, who, between them, managed to shoot eight of the enemy out of the sky, Gabreski wondered how well he would have done in combat. Unknown was the feeling of one who tastes victory in the air. His coveted silver pilot’s wings were untested in combat, in the very place, and on the crucial day, when the Untied States was attacked.

Things were dull in Hawaii, so Gabreski talked his way to being transferred in a few months to the more active “and better supported” European Theater of Operations. He went to England as an intelligence officer, but soon arranged to fly B-24s, P-38s and P-39s, delivering the aircraft to operational units, with the Ferry Command. This lasted a tame three months, but at least he was an active pilot. Then he managed to fly combat missions with Polish Air Force fighter pilots, in Spitfire 9s escorting medium bombers then later GB-17s. Gabreski fired his guns at the enemy only once. The question was still unanswered when the 56th Fighter Group arrived in England. Gabreski joined it as operations officer of the 61st Fighter Squadron. Prior to getting shot down and taken prisoner, the amazingly accurate Gabreski compiled a record of 28 victories in the air plus three on the ground. During the Korean Conflict, he got 6 ½ more in the air. Today, he is the U.S.’ greatest living ace. The question was answered.

Excerpted from the book Above the Pacific by Lieutenant Colonel William Joseph Horvat, 1966.